You Have the Right to Remain Silent

“But, Mom, we didn’t do anything wrong!! Why won’t you listen to me?”

These were the pleading words from my childhood friend, Bev. Her appeals came out as screams between sobs as she sat in the passenger seat of her mom’s car.

Bev’s mom, Mary, was driving us home from the LeMars Police Station.

It was close to midnight on the 28th of December, 1984. Bev and I were 17 years old and we had just gotten busted.

Bev continued begging to be heard with her mom continuing to ignore her. Mary’s eyes stayed affixed on Highway 3 as she drove us back to our respective homes in Remsen, Iowa. With a stoic face glaring into the darkness, Mary was unaffected by her hysterical daughter.

In the backseat, I was also sobbing. My tears were focused on pleading innocence to my own parents. I would soon face them as Mary’s car approached the town lights of Remsen.

The night began like a typical teenage weekend. Best friends since we were three years old, Bev and I were now enjoying the last few months of our senior year. The Remsen St. Mary’s class of 1985 comprised of forty-four students, together completing our adolescent years before being turned loose into the world.

It was a bitterly cold night. Just a few days after Christmas, Bev and I were ready to hang out with friends after spending mandatory time at home for the holidays. With no known parties planned for that night and with the low temps, there weren’t many options for socializing. Wanting to get out of town, Bev and I decided to drive nine miles to LeMars where Bev’s older brother, Rich, had an apartment.

After quietly watching some cable television, a new viewing option of the 80s, we found ourselves bored with just hanging out at Rich’s. Bev and I decided to walk around outside to see if anything was going on in town. Rich also left to find something better to do on a Friday night than hang out with his high school sister and her friend.

With the frigid air and our lack of heavy coats, Bev and I quickly changed our minds about outdoor activity. Back to Rich’s apartment, we found no Rich and a locked door. We were stuck outside. This was the 80s long before cell phones. Not only did we not have a phone to call Rich, but if we even went to a pay phone we wouldn’t know who to call.

Our resolution was to walk toward downtown and find some other Remsen teens who drove to LeMars out of boredom. It didn’t take long for Bev to recognize the car of her next-door neighbors, Krissy and Susie. Relieved to find a ride, we jumped in their car.

Through the commotion of explaining our situation of getting locked out and Krissy finding a place to pull over, we heard a yell outside the car. Walking toward us in the car was Frankie, the town pervert.

“Do you girls want to see some jazz?” he yelled our way.

With Bev and I barely in the car, Krissy laid on the gas pedal. Ready to break into laughter at the comedy of the situation, we instead saw the horror of flashing red police lights directly behind the car. Our thoughts quickly went from the location of Frankie to the proximity of the beer cans in the car. As Susie rushed to hide the evidence, an opened can spilled onto to seat.

The officer approached the car window, as cans were haphazardly hidden. Krissy slowly rolled down her window to greet the police officer with a pungent smell of alcohol.

“It smells like a brewery in here! Do you girls have beer in this car?”

We all gave contradictory answers in unison. The cop then advised us that we were going to the police station. Our offense was the crime of Minor in Possession (commonly known as a MIP in Iowa).

The drive to the station included a crying Krissy running a stop sign and our panicking about what potentially awaited us. Although we were never arrested in handcuffs nor were we put in a holding cell, the tears kept flowing.

Bev and I begged the officers for a breathalyzer test to prove that neither was drinking. Citing our charge of underage possession of alcohol did not require our consuming it, we were denied. Bev and I then tried every tactic from schmoozing to more crying. But none were successful. We were all booked for MIPs.

Our parents were called with Bev’s mom agreeing to pick me up with her juvenile delinquent daughter. Sisters, Krissy and Susie, were picked up by their mom. I became more worried about my situation at home as we got closer to my drop-off. My parents not picking me up was not a good sign.

Walking in the door, I was greeted by my waiting mom but no dad. I immediately started in on my defense. Between sobs of how none of this was my fault, Mom calmly explained that we would talk about it the next day. My dad worked early the next morning and it was late.

The next task at hand was to retrieve my car still parked outside of Rich’s apartment. At 1 am Mom drove me to LeMars. She continued to remind me as I sobbed through my continuous blabbering that she did not want to hear my story. It would have to wait until my dad was there too. The sides were already formed. No one listening to me.

Mom has referred to this car ride as my ‘Tammy Faye episode’ as my non-waterproof mascara stained my entire face with streaming black tears.

Feeling more and more the victim, I woke up my older brother, Mark, when I got home. He and I were close. Mark was my advocate. He would totally understand that I was just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Through tears, I told him about the locked apartment and Frankie encounter. Then I explained how just a few minutes in a car with alcohol led to me at the police station.

Pausing for dramatic effect, I waited for Mark’s sympathetic response.

Mark: “Well, this makes up for all the times you should have gotten your ass in a sling.”

Without another word, he walked back into his bedroom and closed the door.

I sat in shock realizing that my loved ones were abandoning me one by one. It was me against the world.

Saturday afternoon I got another chance to plead my case. This time it was my parents together.

Mom and Dad listened as I told them my story of me doing nothing wrong. Then they gave me my punishment.

My car was taken away indefinitely. I was grounded. And I needed to go to the school principal to receive the school’s reprimand. Of my entire dramatic explanation of events, my parents only acknowledged the part where I was charged with a MIP. End of story.

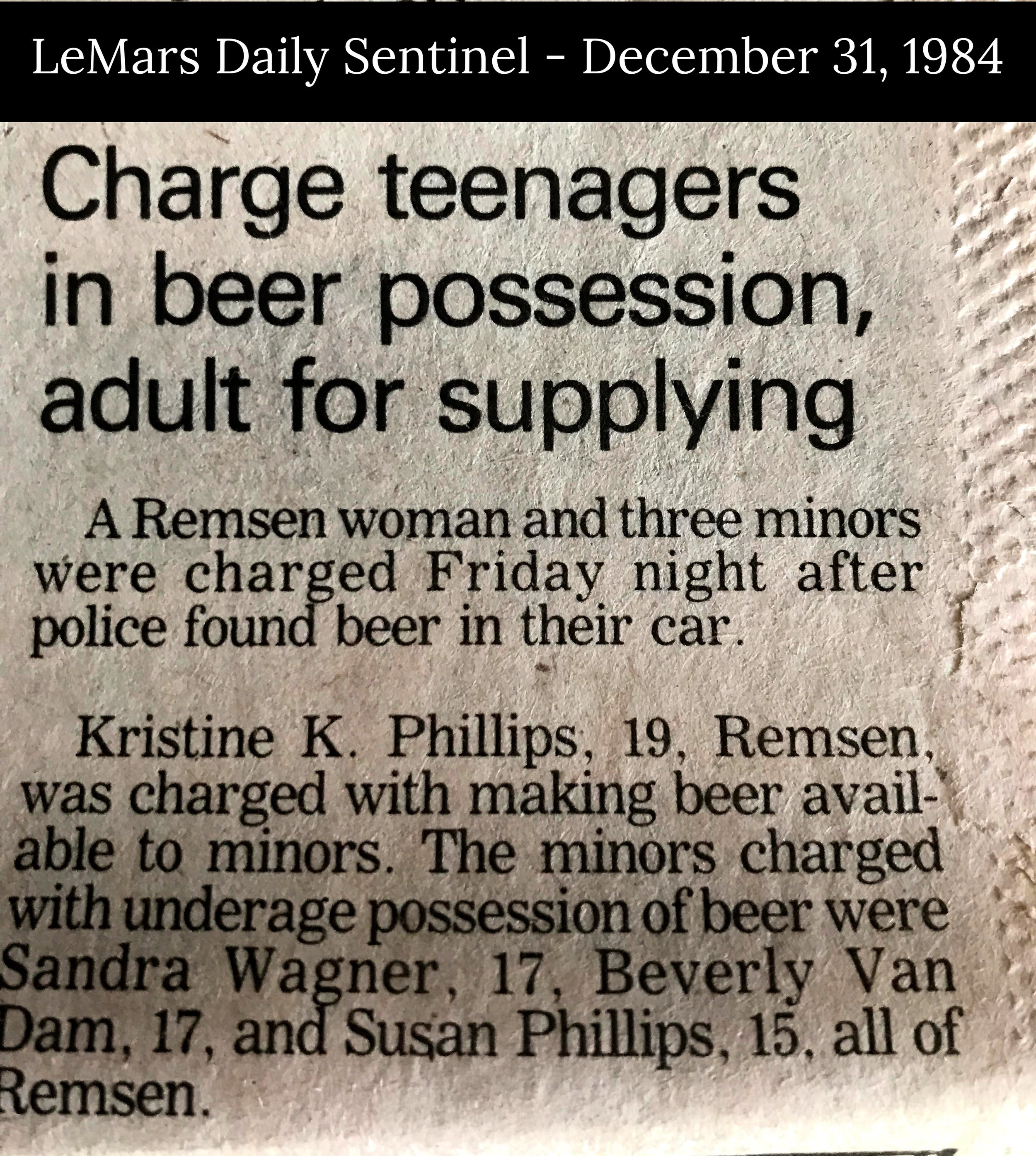

Things went from bad to worse on New Year’s Eve when the LeMars Daily Sentinel published a story with the headline “Charge teenagers in beer possession, adult for supplying”. All four charged had our name, age, and hometown listed. I now felt like it was me defending myself to the ENTIRE world. No one was on my side.

Instead of being spotlighted as a great student and stellar teen, I was instead highlighted as a juvenile delinquent. Worrying about who had read the news article, I was even more motivated to defend myself.

Back to school after Christmas break, I sought absolution from my favorite teacher. Writing a detailed journal account, I gave the play-by-play of my fateful MIP night (Note: The original journal entry is in the link at the end of this story).

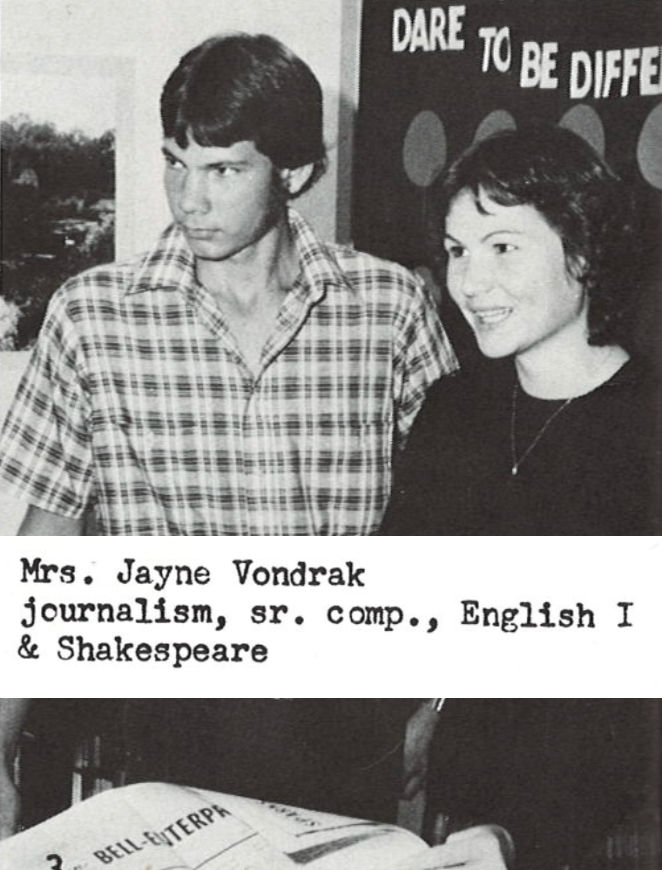

My beloved Senior Composition teacher, Mrs. Jayne Vondrak, was young and understood these things. She would be the one to tell me that I did NOTHING wrong.

In a rambling four-page attestation of the events of the night, I thought I had clearly laid out my innocence. If our school had a debate team (which we did not), I would have been a winner with this piece.

I turned in my journal and it later came back to me. The reading of my entry was verified by Mrs. Vondrak’s red-inked comments at the end of my journal entry.

Mrs. Vondrak: “At some time, we all pay for a stupid mistake. You have a lot to be thankful for. Something even more serious could have happened.”

This response caused me to pause. My belligerence in declaring my innocence began to wane… Maybe I shouldn’t have gotten in the car. I never thought that someone could have gotten hurt.

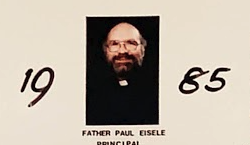

The last stop of my first day back to school in 1985 was a trip to the principal’s office. As part of my home punishment, I knew I had no room to procrastinate on this required meeting.

Our school principal, Fr. Eisele, calmly asked me what happened. He then sat back and listened. For the first time, I told my story with no defensiveness or embellishments leaning in my favor. My expectation was that I would be suspended from all high school activities, including cheerleading. I awaited my punishment.

Then Father did something I didn’t expect. Without placing blame, he said that pulling me from activities my senior year was too severe a penalty.

"Sandy," Fr. Eisele told me sternly "you are a good girl, but you should have known better. No excuses. You knew there was alcohol. You looked the other way and now you're in trouble. But here's what we're going to do...."

Father went on to coach me on what to tell others about my punishment. He told me to say that he originally gave me a strict sentence of a ban from cheerleading and school activities. But after my asking for forgiveness and promising not to make the same mistake again, he showed me mercy.

I felt a change in momentum by my telling the truth. The conversation turned when I was not stuck in a place of defensiveness but instead in a place of wanting forgiveness.

I stopped defending myself. No more pleading for people to hear my side. I finally chose to remain silent.

For the next couple of weeks, I suffered through long cold walks to the school activities for which I gratefully wasn’t banned. Being without a car in the middle of a Midwest winter was a punishment that I endured. I got my car back in Mid-January with mercy given to me this time by my own father.

The entire MIP fiasco was slowly blowing over. Until it wasn’t.

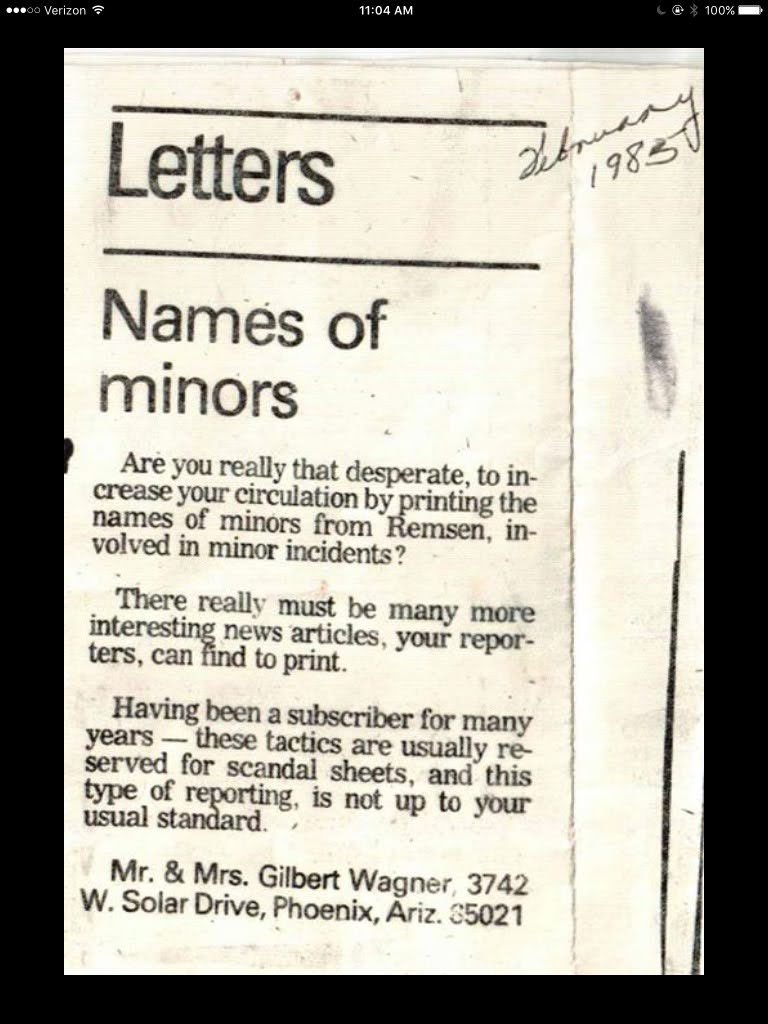

Once again, I was highlighted in the LeMars Daily Sentinel. This time I wasn’t called out by name, but in a published letter from my grandma. In her letter to the editor, Grandma publicly aired her angst with the paper in their choosing to print names of ticketed minors.

My initial response was one of embarrassment at having my MIP front and center again. But my feeling quickly moved to one of being loved through her published words.

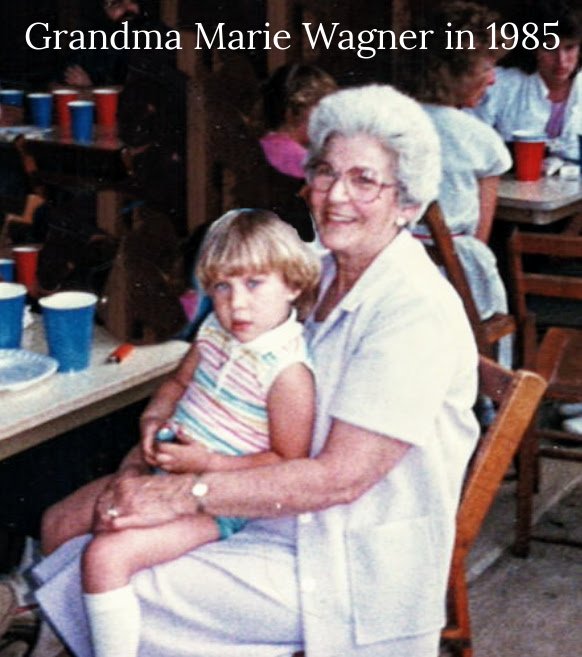

Grandma had my back without me even pleading my case of innocence. We never shared a conversation about that December 28th night in LeMars. She and Grandpa spent their winters in Arizona. What little she knew either came from my parents or the original article in the paper forwarded to her winter address. What she was clear on was her belief that the paper erred in the printing of names of minors.

When the MIP drama finally became old news, I received a letter in the mail with an Arizona postmark. Grandma wrote me a letter and included a cutout of her published letter to the editor.

The letter professed her love for me, her cherished granddaughter, and that she would always stand by me. “Mistakes happen and you are lucky that it didn’t have a worse outcome such as a bad car accident…Keep your chin up! Love, Grandma”

My dad has often made the statement “Don’t defend yourself if you’ve done nothing wrong.” I’ve found this to be great advice over the years. After thinking back on my MIP debacle and how determined I was to profess my innocence, I think of the flip side of this phrase.

Are those who vehemently defend themselves more likely to be guilty? The truth is likely somewhere in the middle.

What I learned from my early criminal record (although notably clean since the 80s) is that it’s better to explain myself factually than defensively.

And then there are those times when I should just remain silent.

Link below to my play-by-play reflection of my MIP just days after it happened (such drama!)…

Memory captures from the time of this story…