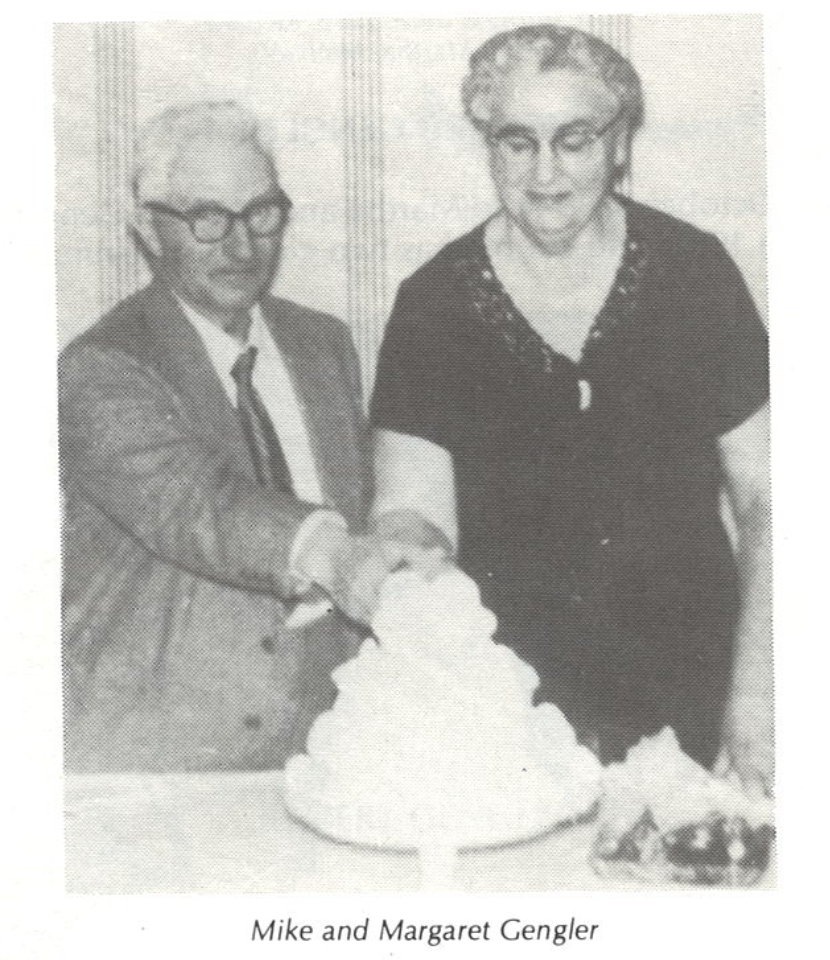

Mike and Vernie

Mike and Vernie’s front porch (this photo was taken in 2004)

I have a childhood friend who asked me to write a story about Vernie, an icon of sorts from our hometown. This request continues to pop up as I publish new stories about our 70s-era adventures in Remsen, Iowa.

“You should write about Vernie!”

When I was back visiting my hometown last fall, I drove by Vernie’s house and was reminded of my memories in this house. But my story isn’t about just Vernie. It’s a story about Mike and Vernie.

I grew up at 119 Harrison Street in Remsen, population 1,678. My house was on the north side of town, close to the railroad tracks and across the street from the fire station. Living a few blocks from Main Street, my dad, the town barber, would ride his bicycle to his shop each day.

Just south of our home was the church and grade school. On our walk to St. Mary’s Church, we would pass one of the largest houses in Remsen, 202 Harrison Street, which was home to Mike and Vernie from 1954 to 1982. With its close vicinity to downtown, this corner lot was bustling with foot traffic.

Our family would walk by the big corner house each Sunday for church. My brothers and I would walk by it each weekday for school. Trips to the library, post office, or city hall usually required passing by this huge home. Children raised in Remsen through the 70s remember Vernie standing on his porch handing out suckers to children.

“Wanna sucker?” was his call from the porch as each child walked by.

Mike was the dad and Vernon was his son. On the good-weather days of the Midwest, Mike and Vernie would pass their time rocking on their porch. In their matching wooden rocking chairs, they would move in perfect unison in their laid-back days of post-farm retirement.

In his 90s and with severe hearing loss, Mike was still able to watch over his disabled son. Vernie had the body of a 40-year-old man but the intellect of about an eight-year-old. As Vernie handed out suckers to children passing their corner, Mike kept a watchful eye from his rocking chair.

“Wanna sucker?” Vernie would repeat, yelling from the porch like the town crier. Mike would monitor as children agreed to the sugar treat with outstretched arms.

In looks, you wouldn’t know at first glance that Vernie had a disability. Other than the shuffling of his walk and the immaturity of his talk, his physical appearance bore no noticeable clues. Yet his mental age differed widely from his physical age. He was a child in a man’s body.

Many of my friends thought only of Vernie as the funny sucker guy. They would go by the house for both entertainment and the treat.

“Hey, let’s go to Vernie’s and get a sucker!”

For me, it was more than Vernie on a porch. It was always Mike and Vernie. There was not one without the other. My interactions went beyond sucker gifts. My family went into their home. My earliest memories include my parents helping out with Mike and Vern.

My dad was the town barber. As was common in small towns, he would make house calls for haircuts. This would include the nursing home as well as the funeral home when requested. Dad would also go to the homes of those too sick or too old to make the trek to his barber shop on Main Street. Mike was one of these customers.

When a haircut was needed, my dad would stop at Mike and Vern’s on his way home. On his bike with tools in tow, he would cut their hair in the comfort of their home. When Mike’s aging hands became too shaky for putting medicine in Vernie’s eyes, Dad took on this task as well.

The eye drops were always a mystery to my youthful observation. They required daily stops by my dad with Vernie anxious for the attention. I would overhear my parents talk about the medicine being just water that both calmed Vernie and gave him something to do.

I would often ride my bicycle to my dad’s shop at the end of the day to join him on his ride home. Helping him clean up while listening to the conversation with his last customer, I would secretly hope for a treat on our way home. Root beer from one of the Main Street taverns or an ice cream cone from the drive-in were both potential stops.

The part of the routine that was always consistent was a final medicine stop at Mike and Vern’s. I would watch in curiosity as Vernie would come to the door with his medicine bottle followed by my dad carefully administering the secret water. I was of an age then that matched the intellect level of the grown man of Vernie. I was confused in understanding what was wrong with Vern.

Soon the daily eye medicine application in the evening was not enough. Vernie started calling our house during the day. Our phone would ring frequently with eye-drop requests.

“Medicine in my eye?” was the blurting question after I answered the phone with a soft “Hello”.

Once my mom gave her approval, I would tell Vernie he could come to our house. Minutes later there would be a knock at our door with Vernie and his ‘prescribed’ drops waiting for my mom. This routine continued throughout my childhood years.

By the time I was ten years old, Mom and I started cleaning Mike and Vernie’s house. Once a month, Mom would load up her buckets, rags, and cleaning supplies, and then with me in tow we would complete a thorough house cleaning of the big house on the corner.

The house seemed humungous when I stepped inside. With my dad, he and I stayed in the back kitchen. With the cleanings, we were in every room. The first time I ventured through the house with a dust cloth in hand, Vernie and I stared at each other in equal wonder. Although there were many relative visits from nearby farms, it wasn’t often under Mike’s watchful eyes that strangers, let alone children, came into the house. I was as much in awe to be walking around Vernie’s house as he was.

With my age of ten, two years older than Vernie’s stagnant mental age of eight, I started to look at the situation through an older lens. This was a paid position that Mom and I took on professionally as we went through our checklist of cleaning steps.

Being inside the house was an education for me, in both history and parental instincts. My mom gave me jobs that kept me close to her. Mike was always out in the wide-open living room with an eye on Vernie. As with the matching wooden rocking chairs outside, they had a similar setting in the living room. Two rockers sat in front of a blaring television beside a large picture window. Mike’s hearing loss required the TV volume at its highest level. I could listen with clarity to episodes of Rin Tin Tin and Gunsmoke as I dusted two rooms away.

My typical jobs were dusting, window washing, and kitchen floor mopping. I would inspect the many framed family photos while removing the accumulated dust specks. Asking my mom questions about Vernie’s mom/Mike’s wife, I learned that her name was Margaret. She was very well-liked in the community.

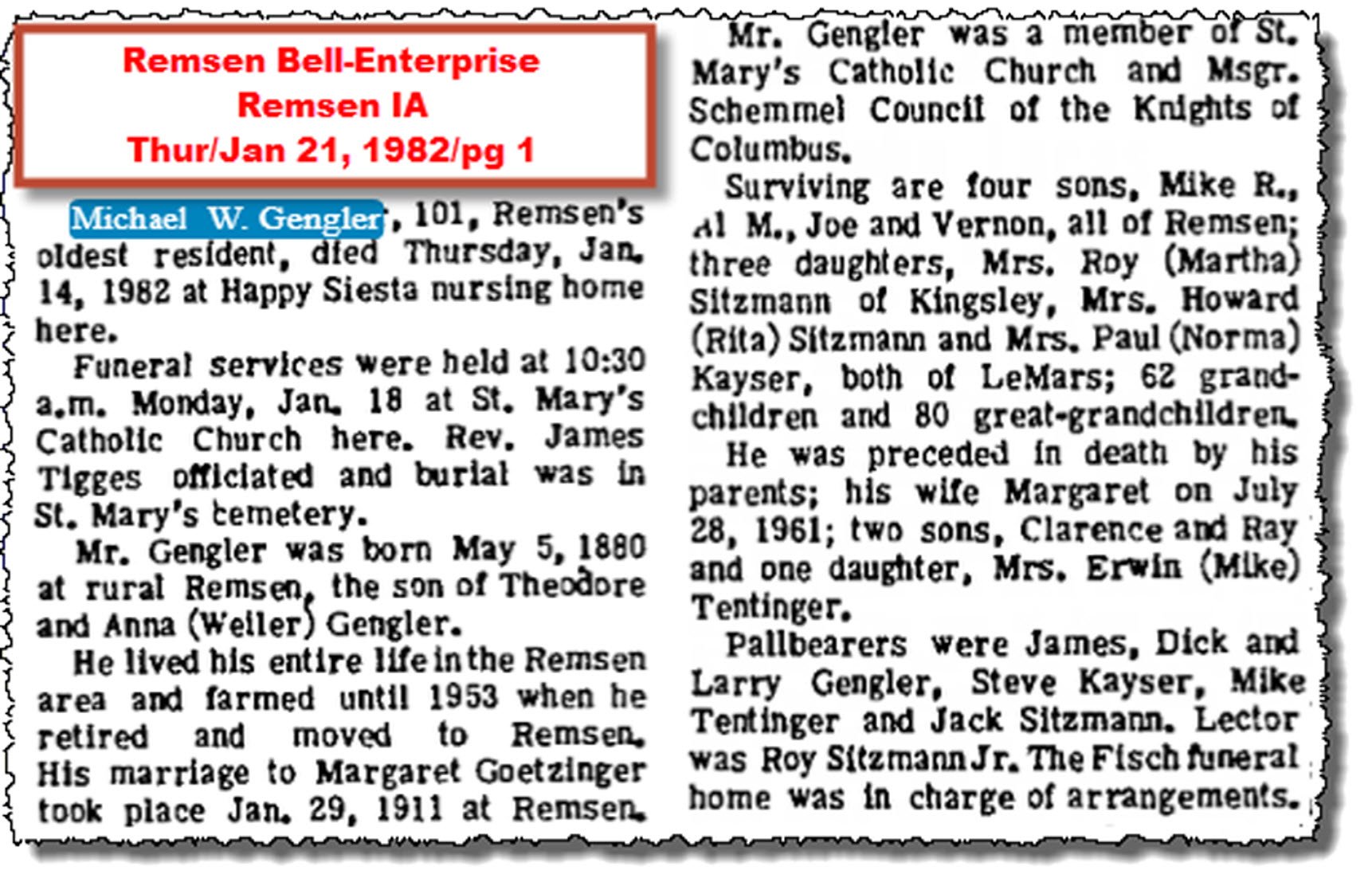

Margaret died at age 70 just seven years after she, Mike, and Vernie moved from their family farmstead to this beautiful home in town. Vernie was the youngest child of Mike and Margaret’s ten children. Mike was 54 and Margaret 43 when their son, Vernon, was born. Mom didn’t know what led to Vernie’s disability, just that it began at birth.

Inside their home, I watched Vernie act as a spoiled child to his dad, throwing tantrums when he didn’t get his way. Mike was in his mid-nineties during our housecleaning years. He would calmly talk Vern through these outbreaks although frail and almost deaf. Vernie had a great fondness for his dad and would ultimately listen to what he was told.

An antic of Vern’s was to overflow the toilet for attention. We would arrive at the house to a panicked Vernie pointing to the bathroom. Mom would find an entire roll of toilet paper shoved in a flushed toilet.

Mom later noticed in the basement that bottles of Coke were stored under the bathroom of this frequently overflowed toilet. She also noticed in the cleanup that the water would drip through to the basement and onto the unopened bottles.

After that discovery, I was never allowed to drink the bottle of Coke given to me at the end of our cleaning day.

Vernie also liked to offer wine and candy on holidays. This would also happen when my dad would stop by for haircuts or eye medicine. He really wanted me to try the Mogen David poured into a fancy crystal glass. My mom would try to explain that I was too young but Vernie didn’t understand. To divert attention I would show inflated enjoyment over the chocolate-covered cherry that I took out of a freshly opened box. Not only would this move the focus from the wine but it would lead to another serving of candy for me.

Once Mom and I went into the basement to retrieve something for Mike. I was in awe to see an open cupboard with no less than 30 bottles of Mogen David wine lined up on a shelf. Cheap red wine and chocolate-covered cherries will always take me back to the house of Mike and Vernie.

Around the time I was thirteen, I took a job at the drive-in by our house. By this time, I was also busy babysitting and didn’t join my mom in the house cleaning job. The drive-in was a daily stop for Vernie in the seasonal months when it was open. He would pick a meal for himself and his dad. He would vary his take-out from taverns to hamburgers, with the loose meat sandwich (called a tavern in Iowa) his first choice.

When working the drive-in, I would know when Vernie was approaching with the sound of his shuffling feet on the graveled alley outside the opened drive-in window. He would frequently clear his throat which was another signature sound of Vernie’s arrival.

Always hoping for a glimmer of recognition or a smile, I would warmly greet him and ask if he wanted taverns or hamburgers that day. He would shyly reply with his order but never acted like he knew me. I never knew if this was a game or if Vernie really didn’t recognize the once-little girl, now a teenager, who used to spend hours in his home.

Going by his house during our junior high years, kids would often yell up at Vernie in a more-teasing way.

“Hey, Vernie… can we have a sucker??”

Mike would still be rocking in his outside rocker, now in his late 90s, and not hearing a word.

No one was ever mean, but there was cynicism in pointing out that we were no longer children. We were now snarky teenagers. But Vernie remained a child. He was only focused on the suckers in his hand.

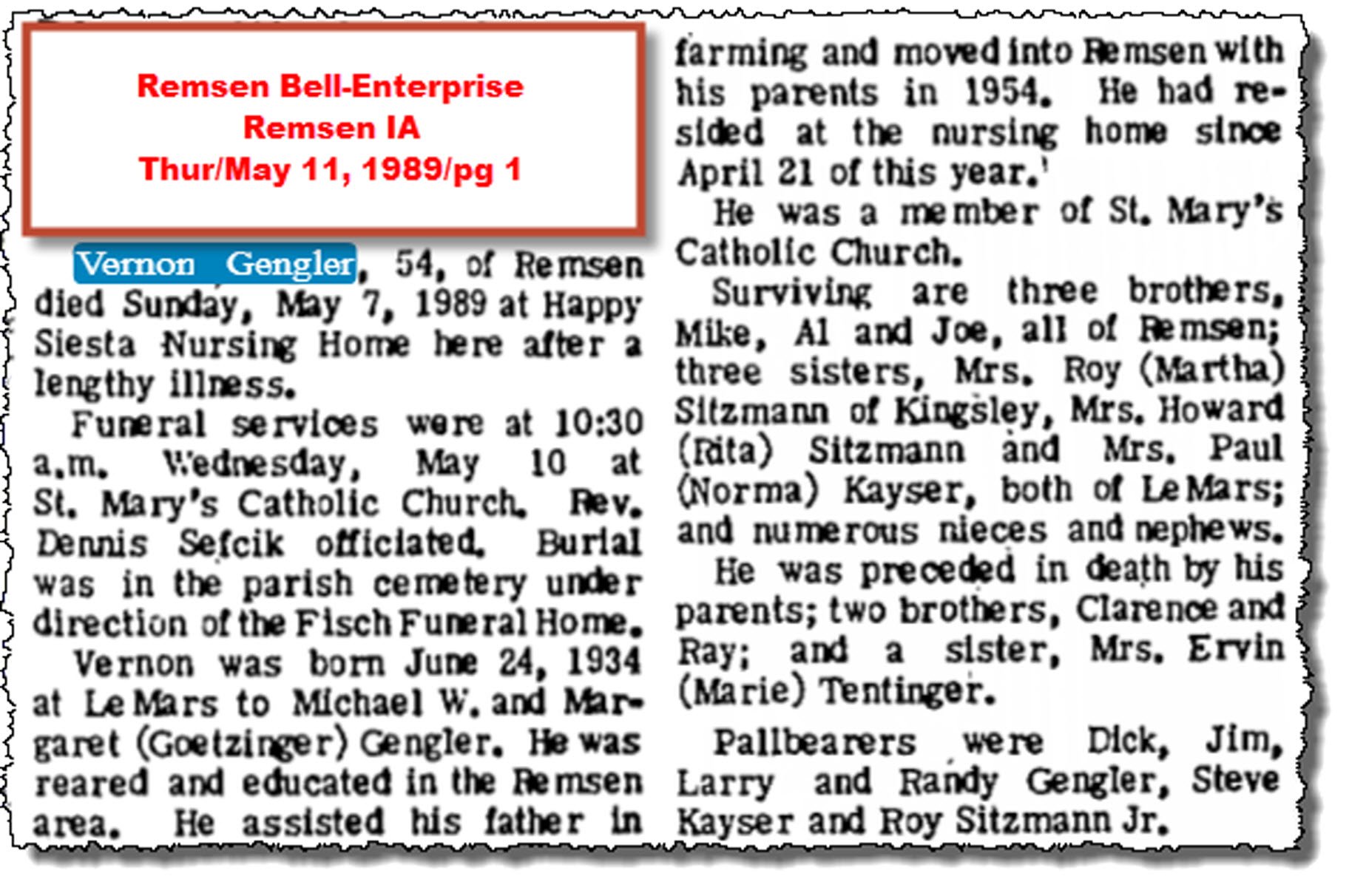

Right before I entered high school, Mike and Vernie were moved into the town’s nursing home, Happy Siesta. Mike died two years later at the age of 101. He was the oldest living Remsen resident at the time of his death. Vernie died six years later at the age of 54.

Vernie died at the same age Mike was when Vernie was born. Mike then went on to spend almost fifty more years caring for a child who never grew up. And most of those years were as a single parent.

I often wondered if Mike stayed in such good health, holding on to life for so long because of his responsibility of Vernie. Was it a promise to his dying wife? Was it his knowing that ultimately Vernie’s love was directed only at him?

Although disabled in mental capacity, Vernie had a healthy body. Even with apparent physical health, he didn’t live long after his dad’s death. The official cause of death was pneumonia. I personally believe that a broken heart was a contributing factor.

There were many lessons learned as a child through my time with Mike and Vernie. I saw how parental love runs deep but the necessity of parental oversight is a needed compliment to this overarching love. Vernie was watched with a careful eye, whether by Mike or my mom or dad. He was not scorned and I was given the great lesson of human acceptance. I saw firsthand how it really does take a village to help those in need. That is the heart of small-town living.

Photos I took touring Remsen on a visit in 2004 - Places noted in the story

News and Obituaries of Margaret, Mike, and Vernie Gengler